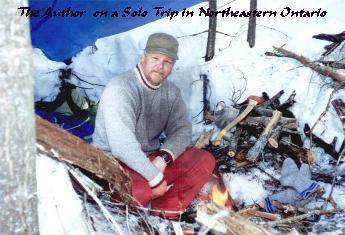

by Earle Jones

It's early March in Northern Ontario. A good 3 feet of ice shrouds the lakes

and rivers insulated by 5 more feet of enduring snow. Winter has taken it's toll on the

populace and is the subject of constant conversation everywhere you go. The general

consensus: When will it end? The days are getting noticeably longer and the sun feels

warmer on the modest amount of exposed skin but no respite emerges. While most are

dreaming of warmer weather, the beach, boating, canoeing, camping, and barbecuing, this is

the time to explore an often neglected activity. Winter Camping!! Brrr! First let's look

at the most obvious pros to such an adventure. You can leave the bug dope at home. It

rarely rains on your parade. Bears are catching some z's so they're not a problem. Food

doesn't spoil as quickly. Since there is an abundance of building material around in the

form of snow, a tent is a non-essential item. Firewood is easier to come by because the

lakes and rivers are frozen and overhangs are accessible. Now the cons. Unlike summer

camping, a lack of preparedness is more likely to kill you. There are new hazards that you

need to contend with such as large quantities of snow dropping from overhead trees.

Crossing creeks and fast flowing rivers with thin ice can create deadly situations if you

are not prepared for them in advance. But all in all winter can be a beautiful time to

enjoy the unhurried pace of camping and, with proper planning, a very memorable

experience. So sit back and find out if unpacking that camping gear early is for you.

It's early March in Northern Ontario. A good 3 feet of ice shrouds the lakes

and rivers insulated by 5 more feet of enduring snow. Winter has taken it's toll on the

populace and is the subject of constant conversation everywhere you go. The general

consensus: When will it end? The days are getting noticeably longer and the sun feels

warmer on the modest amount of exposed skin but no respite emerges. While most are

dreaming of warmer weather, the beach, boating, canoeing, camping, and barbecuing, this is

the time to explore an often neglected activity. Winter Camping!! Brrr! First let's look

at the most obvious pros to such an adventure. You can leave the bug dope at home. It

rarely rains on your parade. Bears are catching some z's so they're not a problem. Food

doesn't spoil as quickly. Since there is an abundance of building material around in the

form of snow, a tent is a non-essential item. Firewood is easier to come by because the

lakes and rivers are frozen and overhangs are accessible. Now the cons. Unlike summer

camping, a lack of preparedness is more likely to kill you. There are new hazards that you

need to contend with such as large quantities of snow dropping from overhead trees.

Crossing creeks and fast flowing rivers with thin ice can create deadly situations if you

are not prepared for them in advance. But all in all winter can be a beautiful time to

enjoy the unhurried pace of camping and, with proper planning, a very memorable

experience. So sit back and find out if unpacking that camping gear early is for you.

The first thing to ask yourself is how do I want to transport myself and my gear over the frozen back-country. Snowshoes or skis? Snowshoes are a good method of travel because you are not limited to where you can go. Snowshoes offer good flotation on almost all snow conditions and, with very little experience, are extremely maneuverable. The enlarged footprint offers matchless stability with a heavy pack and most snowshoe harnesses will fit on standard pack boots with no modification thus eliminating the need for a second pair of boots. Although movement is much slower, photo opportunities can be greater and the silence with which one can move increases the chance of wildlife sightings. On the down side, though, traditional wood and rawhide snowshoes can become extremely heavy and loose in wet snow conditions. Boots tend to slide around in the bindings and a large portion of energy is lost through slippage and lifting the added weight. Skis on the other hand are quicker than snowshoes and, with the right waxes, mild temperatures are not a problem. Ski poles also offer added stability and balance. One of the drawbacks of skis is the need for an extra pair of boots. Also some areas accessible on snowshoes are impossible to reach on skis. Falls can be more dangerous due to increased speed and clumsiness of a pack.

The sleeping bag should be your most expensive investment since it is where you'll spend almost half your time in the bush so don't skimp. I recommend a good quality mummy shaped sleeping bag with a comfort rating of at least -17C. Although more constricting than the standard rectangular shaped bag there is less air inside the bag that your body must heat up before you're comfortable and less bag means less weight and bulk on your back. Just remember that to get the equivalent warmth of a 5 lb mummy bag you would need a 7-10 lb rectangular bag. There are many excellent synthetic fills available on the market such as Lite Loft, Polar Guard HV, Micro Loft which offer admirable insulation properties, but for the best warmth to weight ratio goose down cannot be beat. A good quality down sleeping bag, well cared for and cleaned will last decades and lose absolutely no loft. (thickness of the fill) Synthetic fills can lose up to 25% of their loft in just a few uses and this can be unsettling on those unexpected cold nights. On the negative side, Down must be kept completely dry at all times or it's insulation properties are lost. Synthetics, on the other hand, will be wet but can be wrung out and continue to offer some degree of warmth. Personally a wet sleeping bag will be cold no matter what is inside it. The golden rule: Use utmost care in packing your sleeping bag to keep it dry. Your life may depend on it.

Having a great sleeping bag with the highest comfort rating is all fine and good but totally lost if you're sleeping on the bare snow. Almost 75% of your body heat can be lost under you if you have no insulating layer between you and the ground. Ensolite closed cell foam (blue pad) is a fantastic material but it doesn't add much cushioning. A better choice is a self-inflating open cell mattress such as a Therm-A-Rest pad. It gives you the padding of a good quality air mattress and the insulating factor of a closed cell foam pad.

Layer clothing instead of carrying heavy jacket. The largest mistake of many of the people I've taken in the woods with me in the winter has been their inability to determine how much clothing to bring with them. Often the carry two or three heavy sweaters, jeans, cotton shirts and underwear, and a heavy jacket that spends most of it's time in the pack. You can build up a great deal of heat cutting wood, digging a snow cave or just hiking through the woods. When packing for a winter overnight trip layering is the answer to being warm and dry during the whole adventure. For example, as your activity level increases you remove a layer to prevent sweating. When you stop for a break or lunch you put a layer on to prevent chilling. This way you create a thermostat thus keeping your clothing dry and comfortable for the duration of your trip. Ideally during the coldest times you should have everything you've brought with you on and one extra set in your pack. That's efficiency. Keep in mind, as well, that we lose 50% of our heat through our head so cover it with a hat at all times. One final piece of vital gear I always include is a rain suit. Building a snow cave is wet work. It is not very sensible to build a comfortable snow cave to sleep in if all the clothing you brought with you gets wet in the process. After the cave is built the suit makes a great tarp to insulate your sleeping pad from the snow.

This usually raises a few eyebrows when I mention it because most people equate tents with warmth and security. In winter nothing could be further from the truth. In a tent the air temperature will be approximately 5 - 10 warmer than the outside air. This is fine and dandy when the outside air is a balmy 5C but not much comfort in -20 weather. Look around you. Notice all the snow. If you think back on your high school physics class you will remember two key things about water; it boils at 100C and it freezes at 0C. It cannot go above 100 or below 0. Therefore if you were to build a shelter out of frozen water the air inside said shelter should not go much below 0C which is rather soothing with a wind chill factor of -50 pummelling the outside walls. I've built and slept in many shelters of all designs and shapes and, aside from the initial sense of claustrophobia, have slept as snug as a bug in a rug. The biggest problem was keeping the temperature inside the structure from rising above 0 and turning the solid water into liquid water and dripping on me. Building a snow shelter or "quinzee" is a simple task which can take as little as an hour or as much as 3. One thing that remains the same; it s a wet job and rain gear is a must. Start by tramping down an area 10 feet square with snowshoes or skis. Then with shovels, snowshoes or pots simply pile snow on this area to a height of 6 - 8 feet. Allow this mound to settle for a few hours while you gather firewood, arrange your site, dig a kitchen area out or whatever you need to do. Now begin tunnelling into the mound. As you begin to reach the middle of the mound, enlarge the interior. The secret is to make the walls no more than 20 cm thick to reduce the risk of a cave in. This can be easy to determine by jabbing 20 cm twigs into the mound before you begin tunnelling and hollow out the structure until you reach a stick. The wall will appear slightly translucent and the beautiful blue hue of the light filtering through the wall is quite mesmerizing. Create a sleeping platform on the far side of the shelter at least level with the top of the doorway. This will prevent cold air from pooling on the sleeping area at night and keep the drafts to a minimum. A small candle placed in a hollow in the wall will give off a surprisingly large amount of light and heat during the evening. To prevent the potential for meltdown, try to keep the occupants to 2 people. Another method of shelter is a simple tarp suspended between trees and stretched lean-to fashion. Use snow to create walls on either side and position a fire just outside the opening. A stack of logs behind the fire will work extremely well as a reflector and keep you toasty warm... as long as the fire is going. Unfortunately that's the problem. It only works as long as the fire is going. So most of your night is spent stoking and nursing heat from the campfire. This is a superb method on those mild, clear nights where the air temperature is not expected to drop much below freezing and star gazing is the order of the night. This is definitely one of my favourite methods because I don't particularly like sleeping in a snow shelter unless absolutely necessary.

Drinking water in the form of snow is so abundant that it's difficult to imagine anyone suffering from dehydration but it happens all the time in winter. Many people will simply grab a mittful of snow and pop it in their mouth and so begin the inevitable decent to both hypothermia and dehydration in one fell swoop. You see it takes a great deal of heat energy for the body to melt snow in the mouth and so much snow has to be eaten to replenish our lost water that more heat is subsequently lost. Avoid the temptation to eat snow. The cascade effect is difficult to arrest. If you must eat snow to quench your thirst, allow it to melt and warm n your mouth before swallowing. Swallowing snow will drastically reduce your core temperature and you will begin to shiver uncontrollably. The optimum method is to melt snow over a fire or camp stove. Sounds simple but if not done properly this can lead to damaged equipment, burned pots and elevated frustration levels. To begin with snow is light and fluffy and much dryer than one would expect. As a matter of fact it takes 10 oz of snow to make 1 oz of water. But snow is also highly absorbent and when heated soaks up water like a sponge. This will often cause the pot you're using to melt it to scorch. To prevent this start with about 10 oz of water in the bottom of the pot. Heat and slowly add handfuls of snow. Fight the temptation to fill the pot with snow for it will merely absorb all the water in the pot and you will be left with a burning pot of sizzling, spattering snow. I will often keep a pot of water simmering on the fire during my entire stay and simply throw in a handful or two of snow as water is removed for cooking or coffee. Another hint: fill your water bottles with the warm water before bed and slip them in the foot of your sleeping bag and your feet will be comfortable all night and of course you eliminate the chance of your drinking water resorting back to it's solid state. (Just make sure the cap is securely screwed on before doing this. What about the fire, you ask. How do you build a fire on snow. Well, there are many ways to prevent the inevitable sinking into oblivion from happening. First off, lay 4 or five green logs parallel to each other on the well packed snow. I usually carry an old cookie sheet with me and place this over the logs. Now build a small fire on top of the cookie sheet or on the green logs. No matter how green the logs are eventually they will dry and catch fire and your fire will consequently drop out of site and you will have to start the procedure all over again. If you use the cookie sheet you may get an extra few hours out of the green logs. Don't forget to stick a few logs into the snow behind the fire to act as a reflector.

Keeping your feet warm cannot be stressed enough. When I venture out into the bush in winter, even for a day hike, I always carry at least one extra pair of wool socks to change into. Even when my feet feel dry (wool tends to wick moisture away quite efficiently) normal perspiration can soften the soles of the feet making them more prone to blisters. Also wet wool socks may feel dry somewhat but they can saturate the felt liners in most pack boots and they can take forever to dry out. So don't skimp on the socks and change them often. Your feet will thank you.

You'll notice I stressed wool socks as opposed to cotton. As a matter of fact leave everything made out of cotton at home. Although they may be cozy in front of a roaring fireplace or refreshing on a hot summer day, the very reason they are that way can cause hypothermia in the winter. Cotton gets wet, stays wet and pulls heat away when it drys. That's why cotton is so refreshing on a hot sticky summer day. The slightest breeze on damp cotton will make you feel so cool. Think of how it would feel with a -20 breeze attacking you. Most synthetics are designed to wick moisture away from the skin thus giving you the perception of dryness. Fabrics like polypropylene, and Thermax as well as polyester are excellent for thermal underwear. A fleece sweater or zippered jacket will provide more warmth ounce for ounce than anything on the market and if wet, merely wringing it out will remove over 85% of the moisture. I mentioned wools socks and mittens because wool tends to be warm even when wet and does not melt or burn as readily as synthetics. Try handling a hot pot of water or stoking a fire with synthetic mittens and you'll be spending a very stressful few seconds shedding liquid polypropylene from your fingers.

Pack Boots (the kind with the removable felt liners) are excellent for outdoor camping because extra liners can be carried in the event that one pair becomes damp. Also, sleeping with the liners in your sleeping bag or on your feet at night means that you won't be putting your toasty feet into icy cold boots when you wake up.

Don't forget the shovel, and axe. A small Sven saw or bow saw is excellent as well. Many hardware stores sell a folding travel shovel that can be stowed in a trunk for emergencies. While most of them are too flimsy to be of any use on a winter camping trip a few models do hold up to the abuse that you can give them. I prefer to buy a non folding polyethylene or aluminum type and simply strap it on the outside of my pack. That way when I arrive at my prospective campsite I can commence the task of constructing a kitchen or shelter immediately without having to route through my pack to find that elusive folding shovel. An axe, while not vital can make clearing debris and securing firewood much more pleasant as will a portable bow saw. Often in the winter wood will appear dry because the moisture on it is frozen but when you put it on a reluctant fire, the moisture puts the fire out. By splitting logs you can get to the dry, inner parts of the wood and avoid the frustration of a steaming instead of roaring fire. Again these items can be strapped to the outside of a pack but you must take precaution to cover the axe head with a sheath to prevent injury.

You can never have enough rope: rigging tarps, hauling wood, repairing snowshoes and harnesses. The list is endless.

I always carry a small single burner stove with me on my trips. It nests in a two pot set which I need to carry anyway. When you first arrive at a campsite hunger is often the first sensation you experience and a stove can make preparing a quick meal a welcome joy. It's amazing how smoothly the duties of preparing a site can go on a full stomach. Making that morning coffee is heaven when you don't even have to get out of your sleeping bag. (If, of course, you strategically placed everything you'll need including the stove within reach before bed) One can rough it only so far.

One of the first and most easily accessible items in your pack should be a well stocked first aid kit. Secondly, everyone should know what to do with it. Always remember that you are alone. There is no phone or vehicle to transport an injured hiker to a hospital should an accident occur. And although caution and safe handling of all equipment should be observed, things can go wrong. A wilderness first aid kit should be equipped to handle all of the injuries that can occur on your trips, from sprains and fractures to cuts and bruises and burns. You can leave the bee sting kit at home. Back Packs and Safety cannot be done at a department store or through a mail order catalogue. Find a reputable outdoor store with knowledgeable staff who insist on taking the time to "fit" the pack for you. An ill-fitted empty pack may feel fine in the store but fill it with 20 kg of gear and trek 10km on snowshoes and your vocabulary will take on a whole new light. Believe me, taking a few minutes or even an hour walking about the store with a pack loaded with half the products they sell may be necessary to close the deal for you. Your fastidiousness will not go unrewarded for years to come. With regard to pack safety, All multi-day packs are equipped with a hip belt and a sternum strap. The purpose of the hip belt is to take a majority of the weight of the pack off the shoulders and back and redirect it to the hips and larger muscle groups. When properly adjusted the pack will feel almost empty. (well not exactly empty but much lighter) The sternum strap is just that, a strap connecting the two shoulder straps together across your sternum preventing them from slipping off your shoulders. These two devices can make carrying a heavy pack quite pleasant (OK tolerable) but can also create a potentially hazardous situation. When crossing questionable ice always unbuckle the hip belt and sternum straps for your pack. In the event of a break through you can shed you pack quickly and not be dragged to the bottom. This can be a problem even in shallow water where the weight of the pack and the speed of the current can prevent you from standing up. It is much easier to recover your pack after you get yourself on dry land than for your companions to recover it with your limp, lifeless body strapped to it. So now you're ready to go winter camping or at least thinking a bit more about it. Don't take this article as all the instruction you need and go trudging off to a lonely lake in the middle of who knows where. This was meant to spark interest and whet your appetite, so to speak. The reason most people don't try something new is because they don't know how simple it is. When people think winter they often think hibernation, catching up on some reading, eating, putting on weight, vowing to hit the gym more, whipping themselves for not visiting the gym more. Anyway you get the picture. There's a whole world out there and it isn't stopping just because there's snow on the ground. My advice to you; find someone who has spent the night in the bush in the winter (voluntarily, hopefully) and plan a trip together to gain the experience and enjoy a bug free, crowd free, pristine winter experience. You may never pack away the camping gear again.

Learn a little about Earle Jones

Return to The Canoe Camper's Home Page.